You may have heard people describe our sun as ordinary or not special. In comparison to other stars in the universe that may be true, but I submit that to those of us in our solar system the sun is quite special. Let us take a closer look at our sun and then decide if you think it is special or not. Our sun is the only star in our solar system. Eight major planets orbit the sun which is at the center of our solar system. The average distance between the earth and sun is 149,668,992 km or 93 million miles. Astronomers use this average distance as a unit of distance called astronomical units or AU. The distances in our solar system, galaxy, and beyond are so vast that it is easier to calculate distances using astronomical units than it is to use miles or kilometers. The sun sits at the center of our solar system and makes up more than 99% of the mass of the entire solar system. The diameter of our sun is 1.4 million kilometers (865 thousand miles), over one million earths could fit inside the sun. The sun produces heat and light which is needed for life on Earth. Without the sun the planet would freeze and life as we know it, would not exist.

What is Our Sun Made of and What Makes it a Star

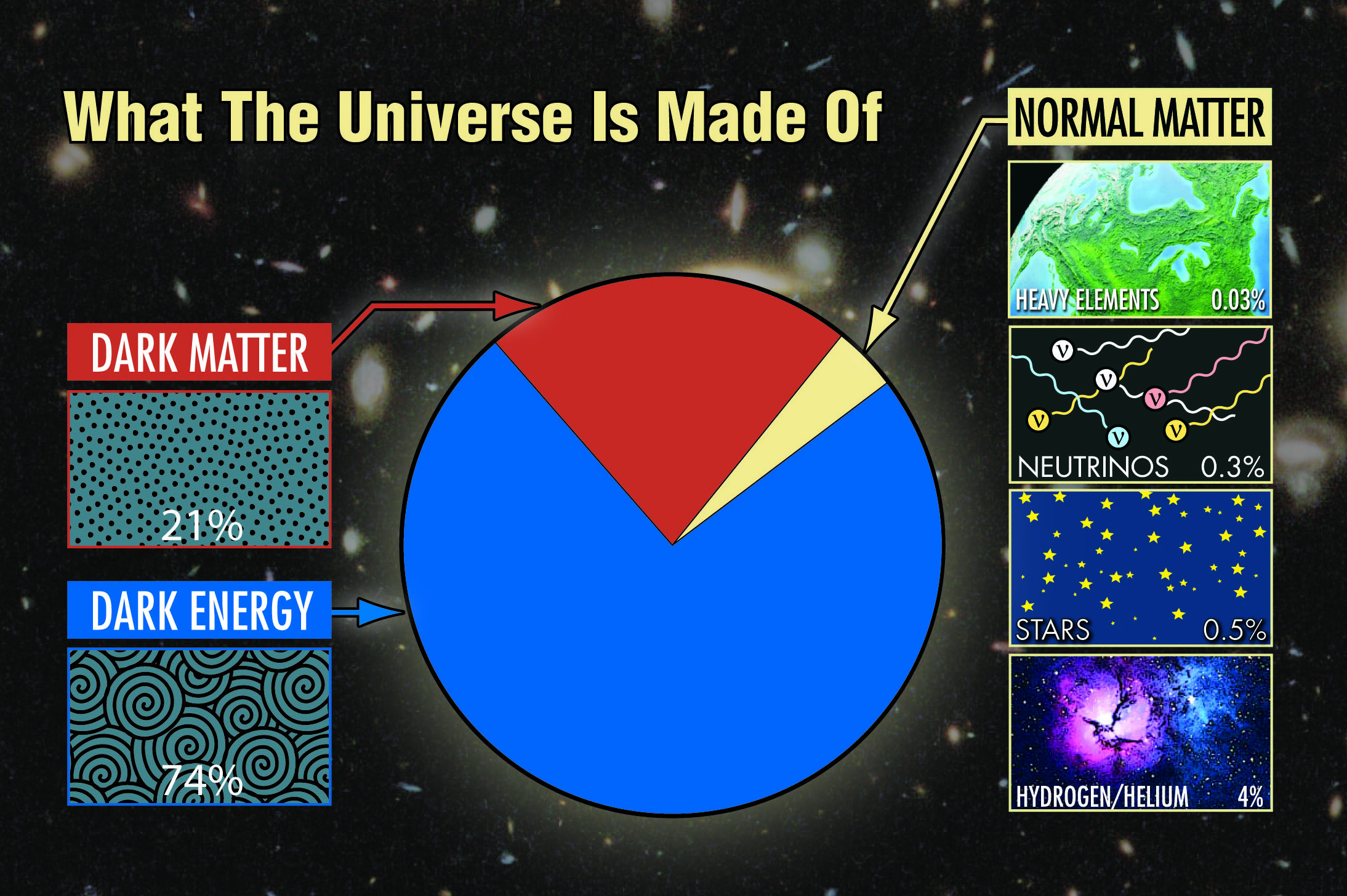

Our sun is a G-class star that was formed some 4.6 billion years ago and is expected to last another 5 billion years. Stars form in a stellar nursery known as a nebula. A nebula is “… an enormous cloud of dust and gas occupying the space between stars and acting as a nursery for new stars (spacecenter.org) The sun, like all stars, is a hot ball of ionized gas. Our sun does not have a solid surface nor a solid core. The sun is 73.4% hydrogen and 25% helium by mass. The sun also contains trace amounts of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, neon, magnesium, silicon, sulfur, and iron (ucf.edu).

What makes our sun, or any other star a star? The object must be massive enough that nuclear fusion of elements can occur in the core due to the immense pressure inside the object. The smallest stars that exist are approximately 10 percent the mass of our sun while “high mass” stars are classified as stars having more than three times the mass of our sun. UY Scuti is the largest star ever observed and it has a radius that is 1700 times larger than our sun and it has a mass 7-10 times the mass of our star. 5 billion suns could fit into a sphere with the volume of UY Scuti.

The Layers of the Sun

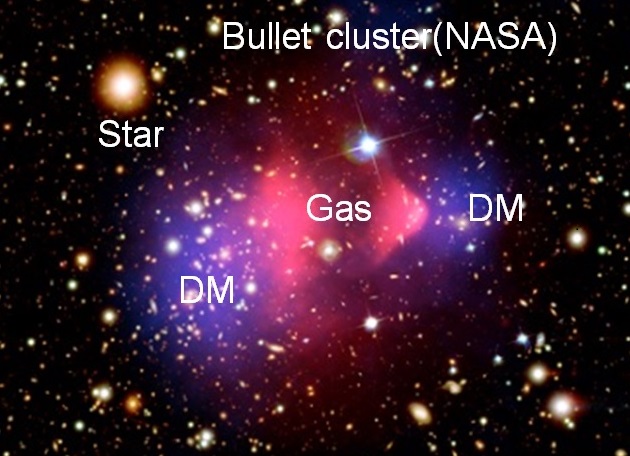

The structure of the sun contains several different layers. The core of the sun is where nuclear fusion occurs as the sun fuses hydrogen into helium through a process called the proton-proton chain. This is a three-step process that results in fusing of hydrogen to produce helium. According to NASA “In the first step two protons collide to produce deuterium, a positron, and a neutrino. In the second step a proton collides with the deuterium to produce a helium-3 nucleus and a gamma ray. In the third step two helium-3s collide to produce a normal helium-4 nucleus with the release of two protons.” A byproduct of the nuclear reactions that occur in the core is the production of elementary particles called neutrinos. Neutrinos, according to scientificamerican.com are subatomic particles that is remarkably similar to an electron but has no electrical charge and a ridiculously small mass, which might even be zero. Neutrinos are one of the most abundant particles in the universe. These reactions are what produce the heat and light that we receive on Earth. The core of the sun extends about a quarter of the distance from the center of our star. The temperature within the core is over 15 million Kelvin.

The radiative zone is the next layer after the core. This region is where energy is carried outwards via radiation. The energy is carried through the radiative zone by photons. These photons, which travel at the speed of light, collide with other particles during their journey to the surface. According to suntoday.org, it takes “several hundred thousand years for radiation to make its way from the core to the top of the radiative zone.”

The convection zone is the outer most layer of the interior of the sun. This zone is much cooler than the core with temperatures of 2,000,000 C at the base of this zone while it is only 5,700 C at the top of the zone. This large temperature difference results in a phenomenon called convection. By definition, convection is “the movement caused within a fluid by the tendency of hotter and therefore less dense material to rise, and colder, denser material to sink under the influence of gravity, which consequently results in transfer of heat.” The convective motion in this zone results in “the generation of electric currents and solar magnetic fields (cora.nwra.com)

The photosphere is the first layer of the sun we can directly observe. This layer is 100 km thick and has a temperature range of 6500 K at the bottom and 4000 K at the top of the photosphere. This region is where sunspots, faculae, and granules are observed.

The chromosphere is an irregular area located above the photosphere. Temperatures range from 6000 C to 20,000 C. In the chromosphere activity such as prominences, solar flares, filament eruptions can be observed. The reddish color seen in prominences is a result of the light given off from hydrogen at the higher temperatures.

The outermost layer of the sun, often called the solar atmosphere, is the corona. This portion of the sun is visible during solar eclipses as the whitish edge of the sun. The corona features things such as loops, streamers and plumes that may be visible during a solar eclipse. The temperature of the corona is 1 million C. This is 1000 times hotter than the photosphere despite it being further from the core of the sun. In 1942 Swedish scientist Hannes Alfvén proposed a theory to explain this temperature anomaly. According to earthsky.org he “theorized that magnetized waves of plasma could carry huge amounts of energy along the sun’s magnetic field from its interior to the corona. The energy bypasses the photosphere before exploding with heat in the sun’s upper atmosphere.”

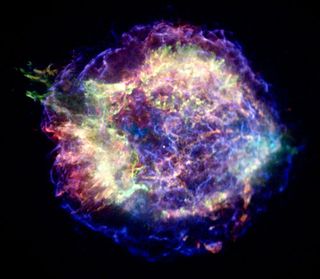

The Death of Our Star

The ultimate fate of a star depends on the star’s mass. High mass stars end their lives by going supernova and becoming a blackhole or a neutron star. Our sun is not massive enough to end its life in such spectacular fashion. When the sun exhausts its fuel, it will “expand into a red giant star, becoming so large that it will engulf Mercury and Venus, and possibly Earth as well (solarsystem.nasa.gov). According to an article published in Nature Astronomy the sun will “… produce a visible, though faint, planetary nebula” (earthsky.org). A planetary nebula is a bit of a misnomer as it is not related to planets. The term was coined by “… William Herschel, who also compiled an astronomical catalog. Herschel had recently discovered the planet Uranus, which has a blue-green tint, and he thought that the new objects resembled the gas giant” (space.com). A planetary nebula, according to Oxford languages is “a ring-shaped nebula formed by an expanding shell of gas around an aging star.” This phase of stellar evolution may last for tens of thousands of years which is a brief period astronomically speaking. Over time the faint planetary nebula will fade, and the sun will cease to shine, and its temperature and pressure will drop. The sun will become a white dwarf about the size of the earth. Is that the end of the cycle? Perhaps not. Astronomers believe that the white dwarf will continue to cool down to a point where it no longer emits light or heat. At this point it will no longer be visible and will be called a black dwarf. This cooling period is thought to take trillions of years so no black dwarfs exist. See my earlier post if you want to learn more about these fascinating objects.