Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is of those topics where people feel confident that they understand it but many people only understand a portion of it. The uncertainty principle is likely the first thing people will mention if you ask them about quantum mechanics. As with many things in science there is actually a much deeper and richer explanation of this phenomenon than you might be aware of. So let’s jump in and learn about the history and applications of one of the most famous and misunderstood topics in physics.

Werner Karl Heisenberg was born on December 5th, 1901 in the city Wurzburg, Germany. Heisenberg displayed an aptitude for mathematics from an early age and it wasn’t until he attended the University of Munich in 1920 that he began his study of physics in earnest. At the tender age of 25 he was appointed professor of theoretical physics in Leipzig. During this time Heisenberg worked with Max Born, Neils Bohr, Arnold Sommerfeld and others to develop and refine the field of quantum mechanics.

In 1925 Werner Heisenberg submitted a paper that in his words “seeks to establish a basis for theoretical quantum mechanics founded exclusively on relationships between quantities which in principle are observable.” This paper helped describe quantum mechanics using the mathematical principles of matrices. This method of calculating the quantum behavior of particles was a tremendous breakthrough in the emerging field of quantum mechanics.

History of the Uncertainty Principle

Before we describe exactly what the uncertainty principle states and describe its applications let’s take a moment to discuss how Heisenberg arrived at this monumental insight. In 1926 a debate was raging between those that held to Heisenberg’s matrix version of quantum theory and Erwin Schrodinger who believed in the wave theory of quantum mechanics. Most scientists of the day preferred the wave theory due in, no small part, to the ease and familiarity with the mathematical equations presented by Schrodinger.

Erwin Schrodinger presented his findings that the wave theory and the matrix theory gave identical mathematical results. As a result of this finding Paul Dirac and Pascual Jordan developed a set of unified equations collectively known as transformation theory which became the foundation for quantum mechanics. While Heisenberg studied how to measure the variables in the unified equations, and with input from Wolfgang Pauli, Heisenberg detected a problem with trying to measure the variables.

Heisenberg noticed that in trying to determine the precise position and momentum of a particle, at the same time, imprecisions appeared. These imprecisions occurred when trying to measure the time and energy variables at the same moment as well. Heisenberg presented his results in a paper to Pauli dated February 23rd, 1927. Upon receiving positive and encouraging feedback from Pauli, Heisenberg formalized and submitted his findings for publication.

What Does the Uncertainty Principle Mean?

Werner Heisenberg attempted to use his matrix mechanics, in a thought experiment to describe the path of an electron in a cloud chamber. He realized that the path the electron traversed was made visible by the condensation of droplets of water that were actually larger than the electrons they were trying to detect. (J Baggott, The Quantum Story p91). The consequence of this meant that the instantaneous position and velocity of the electron can only be approximately known. We will come back to the electron and cloud chamber thought experiment later.

Let’s discuss a few terms that we will need in our explanation of the uncertainty principle. Planck’s constant represented by the letter h and has a value of 6.6262E -34 Joule-second. “Planck’s constant defines the amount of energy that a photon can carry, according to the frequency of the wave in which it travels.” (https://science.howstuffworks.com/dictionary/physics-terms/plancks-constant.htm) Next is momentum which is the product of mass multiplied by velocity. This is important because you will see momentum used in some descriptions of the uncertainty principle and in others you will see velocity. It is more common to use momentum as all particles such as electrons, have a mass associated with them.

Heisenberg had discovered a fundamental property of nature which states “the uncertaintites is position and momentum cannot be smaller than Planck’s constant.” (J Baggott, The Quantum Story p91) This results in a limit to the amount of precision we can simultaneously have regarding the position and momentum of a particle. This fundamental limit does not hold true in our everyday experiences of classical mechanics.

The image above is the equation for the uncertainty principle where x represents position, p represents momentum and the triangle represents the uncertainty. The equation states the product of the uncertainty of the position and momentum must be greater than or equal to the Planck’s constant divide by 4pi. This equation can be rewritten to include the uncertainty of time and energy in addition to position and momentum.

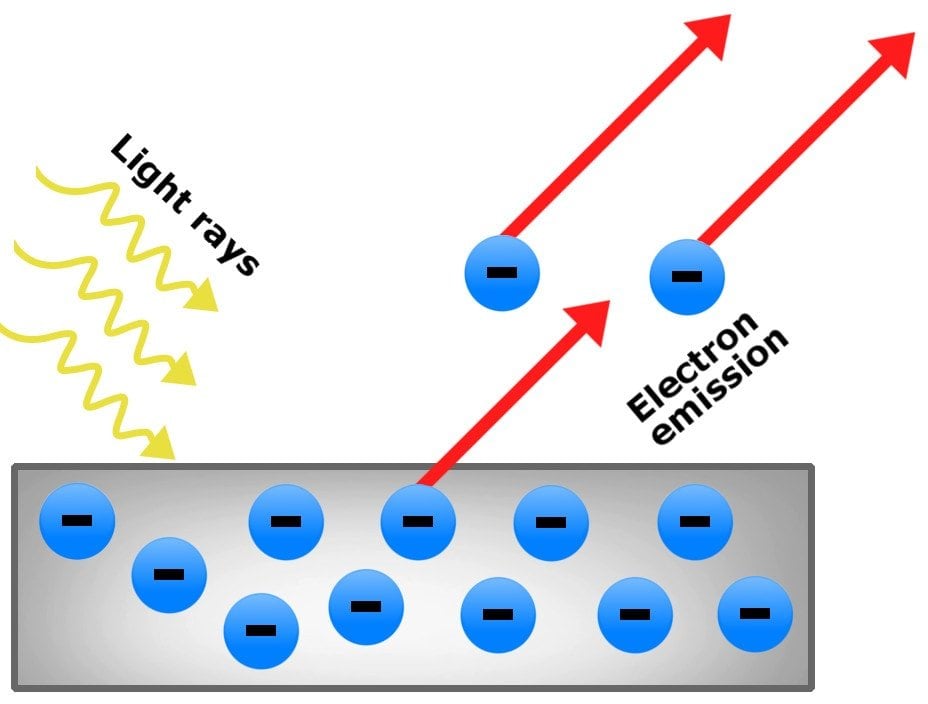

Recall the electron and cloud chamber thought experiment from earlier. One way to measure the position and momentum would be to use a microscope. An issue here is that every time a photon bounces off the electron the momentum and position of the electron is changed. One might be able to determine the electrons instantaneous position, however the large interaction between the electron and the device we are using to measure its position means we are unable to determine its momentum. You may be asking yourself can we use a device with lower energy photons, that is those with a lower frequency or longer wavelength ? This would allow us to calculate the electron’s momentum but we would not be able to accurately measure its position. This thought experiment is useful to give you a conceptual understanding of the uncertainty principle but it is more useful than truthful.

What is really happening here is that because of the wave particle duality it is impossible to know the exact location and momentum of an object. The reason for this is because “what we can measure is limited by the fact that position and momentum are undefined until we measure them in the quantum realm. In the thought experiment with the electron and the cloud chamber the electron has a definite position and momentum prior to making a measurement. In the quantum world, due to the wave-particle duality the precise position and momentum do not exist. (C Orzel, How to Teach Quantum Physics to Your Dog p44). Here is a quick conceptual explanation of the uncertainty principle: https://youtu.be/m8VQue1Nffw

Misconceptions of the Uncertainty Principle

One of the most common misconceptions of the uncertainty principle is that it is caused by the act of measurement. The idea here is that the act of measuring the object causes a change in the position or speed of the object as in the thought experiment. The reality is that the principle is a result of the dual nature of quantum objects.

A second misconception is that current technology limits our ability to determine both the position and momentum of a quantum object. It turns out that the uncertainty principle is a fundamental limit set by nature rather than a technological or observational limit.

What it All Means

The point of all this is that the uncertainty principle, also known as the indeterminacy principle, is a fundamental limit of nature and is due to the wave-particle nature of quantum particles. The concept of an exact position and exact momentum of a quantum particle is meaningless. “Any attempt to measure precisely the velocity of a subatomic particle, such as an electron, will knock it about in an unpredictable way, so that a simultaneous measurement of its position has no validity. This result has nothing to do with inadequacies in the measuring instruments, the technique, or the observer; it arises out of the intimate connection in nature between particles and waves in the realm of subatomic dimensions. (https://www.britannica.com/science/uncertainty-principle) As stated earlier this applies not just to position and momentum but to energy and time as well. Well, I certainly hope you enjoyed this post.